EOED mothballed

Work on this project ceased in 2022 and the website is now static. For Charlotte Brewer’s current OED research, please go to the Murray Scriptorium.

What does the OED tell us about the English language?

Work on this project ceased in 2022 and the website is now static. For Charlotte Brewer’s current OED research, please go to the Murray Scriptorium.

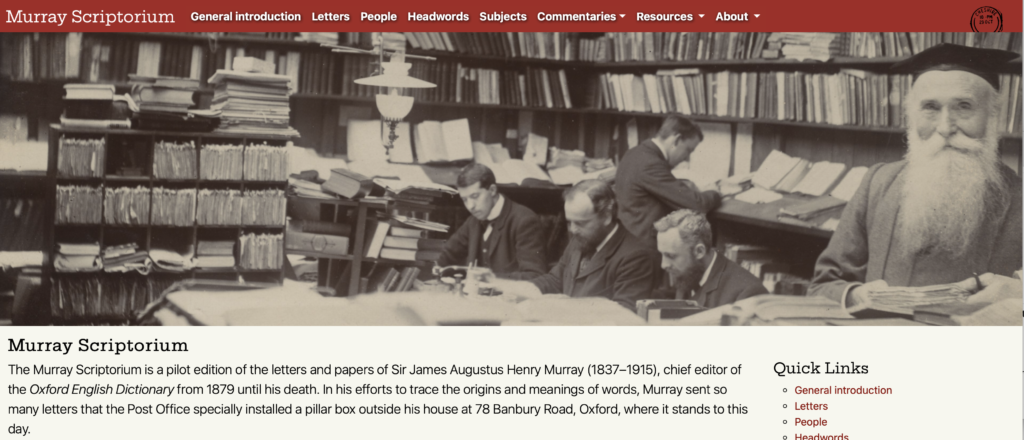

My co-editor Stephen Turton (Gonville & Caius College, Cambridge) and I have just published the pilot edition of the Murray Scriptorium, a long-term project whose aim is to produce a fully annotated and digitized scholarly edition of the correspondence of Sir James Murray (1837-1915), chief editor of the first edition of the Oxford English Dictionary. Much of the research for the OED was carried out though the medium of letter-writing, and Murray wrote so many inquiries to his vast range of correspondents that in the early 1880s the Post Office installed a pillar-box outside his house at 78 Banbury Road, Oxford.

In pursuing the meaning and history of words, Murray exchanged letters with prime ministers (e.g. William Gladstone), distinguished writers of the day (e.g. George Eliot, Thomas Hardy), subject experts and academics both professional and amateur (the Director of Kew Gardens, men and some women of letters such as Professor W. W. Skeat in Cambridge and the medievalist Lucy Toulmin Smith), as well as ordinary individuals whose identity is now unknown (Dear Sir, Dear Madam).

Our pilot edition, designed by Huber Digital, contains a selection of letters transcribed from photographic scans (checked against the original documents where possible) and marked up in XML in accordance with the open-source protocols of the Text Encoding Initiative. Supporting resources include an Introduction explaining the general interest of the letters as well as the role they played in the making of the dictionary, while the letters themselves are searchable by author, recipient, subject, location, etc. Editorial commentaries explain the special character of the dictionary along with some of the features illuminated by individual letters, e.g. the contributions made by women to a largely male-dominated project, the difficulties in including obscene vocabulary, the treatment of World Englishes.

Most of the letters in this initial stage of the Murray Scriptorium are held by the Bodleian Library, part of a huge collection of family papers donated to the library in 1996 by K. M. Elisabeth Murray, the editor’s granddaughter and author of a best-selling biography of him, Caught in the Web of Words (1977). Others have been transcribed from the other main holding of his letters, at Oxford University Press, which employed Murray on the OED from 1879 till his death (when he was part-way through editing the letter T), as well as from smaller collections in public or private ownership. Later instalments will represent both archives more fully as well as those further afield, while enhancing its inbuilt digital resources and expanding the range of topics covered.

Visit http://murrayscriptorium.org to see the holding page for the new Murray Scriptorium project. You can also download an advance copy of the forthcoming article:

UPDATE MARCH 2021: this project will now be funded by the British Academy/Leverhulme Trust

The author of this website, Charlotte Brewer, has just been awarded a grant from the University of Oxford’s John Fell Fund to create a pilot edition of the Murray Papers, pending the result of an application for funding from an external source. I’ll be working on this fascinating project with Stephen Turton, who recently completed an Oxford DPhil in historical lexicography (see Turton 2020a and 2020b).

During his editorship of the Oxford English Dictionary, J. A. H. Murray posted so many letters in pursuit of his inquiries that the Post Office installed a pillar box outside his house at 78 Banbury Road, Oxford. Research conducted by correspondence played a vital role in the construction of this revolutionary new dictionary, published in instalments by Oxford University Press between 1884 and 1928. As Murray himself described, a typical day might go as follows

I write to the Director of the Botanic Gardens at Kew about the first record of the name of an exotic plant; to a quay-side merchant at Newcastle about the keels on the Tyne; to a Jesuit father on a point of Roman Catholic Divinity; to the Secretary of the Astronomical Society about the primum mobile or the solar constant; to the India Office about a letter of the year 1620 containing the first mention of Punch; to a Wesleyan minister about the itineracy; to Lord Tennyson to ask where he got the word balm-cricket and what he meant by it […] In fact a lexicographer if he wants to be accurate, has to be a universal enquirer about everything under the Sun, and over it.

Peter Gilliver, The Making of the Oxford English Dictionary, Oxford University Press, 2016

Many of the resulting documents now occupy the best part of 9 linear metres of shelf space in Oxford’s Bodleian Library. Apart from vividly testifying to the OED’s status as a largescale collaborative enterprise, they are a unique and invaluable resource for researchers of late 19th- and early 20th-century English language and literature, the social and intellectual networks of the OED’s compilers, and the late modern history of linguistics and other disciplines.

Though individual letters have been quoted in a number of articles and monographs on the history of the OED and its compilers, they have never been systematically edited or published. The results will be made freely available in a website, with a view to expanding the project over the next few years to support scholarly and popular interest in the OED as it approaches its 2028 centenary.

Stephen and I will be drawing gratefully on the advice and expertise of a number of Oxford colleagues to pursue this project, including Professor Lynda Mugglestone, Dr Peter Gilliver (associate editor of the OED and author of The Making of the OED), and Bev McCulloch, OED archivist. Watch this space for further updates.

EOED has just completed its series of pages on the OED’s treatment – both past and present – of different periods in the language. The series starts at Period coverage.

Here is a summary of the main points.

To read more, click on the pages below

OED Online has recently put up a new tool on its website at www.oed.com.

The case for visualization tools such as these is that they represent different categories of quantitatively assessed data in a visually striking way. They are especially useful when they indicate groupings or relationships between constituent elements of the data that researchers might not previously have noticed or considered.

The OED Text Visualizer certainly has the potential to do this. Users can type in text of up to 500 words long to see the etymological source of each words (Germanic, Romance, etc) and when it first entered the language.

In its present form, however, the tool is problematic. The major issue is as follows. As its accompanying text explains, the Text Visualizer draws on two important components of OED Online entries: etymological origin of a word, and date of first recorded usage. What is not explained is that just under half of these two sets of OED data are significantly out of date, in some cases by a hundred years and more, since the entries from which they are derived are as yet wholly or partially unrevised.

It follows that the results produced by the Text Visualizer represent an undifferentiated mixture of internally inconsistent lexicography, some of it significantly out of date. The tool needs to be reconfigured so that users can distinguish between results derived from modern lexicographical scholarship (i.e. 2000 onwards) from those based on entries first published in earlier stages of the Dictionary (stretching from 1884 to 1989). In its current form the Text Visualizer delivers results which are not yet appropriate for use in academic research.

The Text Visualizer also provides information on the frequency of use of a word, both in the year the user has assigned to the text and in ‘modern English’. This is valuable, but no account or reference is made to the source of this information, which we may guess to have been Google N-grams, presumably manipulated or adapted in some way. Users of the tool need to know the source of the figures cited so that they can understand the assumptions on which they have been produced. This is a basic requirement for academic research.

One excellent feature of the new tool, nevertheless, is that its results are produced in csv and other formats and hence are far easier to work with for research purposes than the search results currently available on OED Online (see under Search tools below).

A more general comment is as follow. Setting aside the criticisms above, the OED visualization tools so far produced (e.g., geographical origin of vocabulary in English over time) have been captivating but over-determined. That is, they make assumptions about what researchers are interested in. By contrast, it is a widely acknowledged truism that good research comes out of giving researchers free and unfettered access to primary data, so that they can explore and think about it independently. The range of search tools on OED Online already provides a generous range of possibilities for new types of research, though of course we would all like more tools and more/better data to be available (for example, the currently provided information on frequency of head words is unsatisfactory). The problem is that these website tools don’t work well and the results are delivered in an unanalysable format, as described on EOED at OED Online.

OUP is now planning ‘a new suite of tools based on an OED Text Annotator engine,’ of which the Text Visualizer critiqued above is an example. Exciting as such tools are, there are other features of the OED Online website in its current form which are so unsatisfactory as to require immediate attention. Sorting these out is a priority of at least equal if not greater importance than a new set of tools, especially if the new tools repeat the flaws of the existing ones. Here is a list.

Transparency on date of entries and changes to entries

Quotation sources

Search tools

Editorial principles and practice; other accompanying information

November 2019 sees the launch of the new version of Examining the OED. The site has been rewritten and reorganized and lots of new material added – notably under Period coverage, where we look at the changes the new version of OED (OED3) is gradually making to the OED’s picture of the chronological shape of the language.

To find your way around, have a look at our new Contents page and (for a list of all material on the website) Site map.

All feedback and suggestions welcome.